Black History

We believe that to best understand our present and to prepare for our future, we need to learn about and honor those who came before us and paved the way. Oxford's Black community fought for the integration of schools, created a semi-professional athletic team, and raised money to build (and rebuild) churches that still stand to this day and continue to be places of gathering.

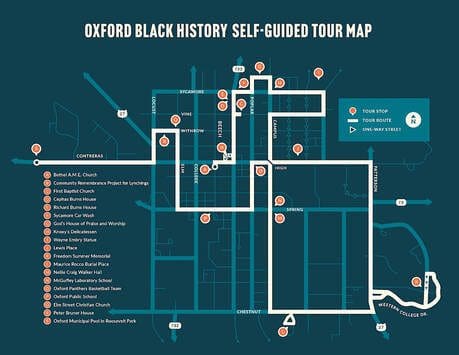

Self-Guided Black History Tour

Oxford, Ohio's Black community has a rich and important history. It is through this self-guided tour that we aim to keep alive the memories of the brave Oxford citizens who fought for their right to occupy public spaces and who flourished in their passions despite systemic racism.

We honor the lives and legacies of those who never faltered in demanding justice. We celebrate and gain inspiration from the accomplishments of Oxford's Black community, then and now.

How to use the guide: The letter next to each title and description corresponds with the letter on the map (seen to the right). Some locations on the tour will not have a clear place to pull over if you are driving, so please exercise caution and park in the closest parking lot if you wish to stop to observe the location more closely. The tour takes roughly one hour to complete.

For a physical copy of this self-guided tour, please visit the Enjoy Oxford office at 14 W. Park Place, Suite C available 24/7, or email info@enjoyoxford.org to have a copy mailed to you.

(Download a PDF file of the Black History Tour)

Audio Tour

Explore Oxford’s vibrant heritage and celebrate Black culture with the Black History Audio Tour! This engaging audio experience takes you through the stories, landmarks, and legacies that have shaped the community. Listen anytime on your favorite platforms, including Listen Notes, Amazon Music, iHeart Radio, Player FM, Podchaser, Boomplay, and Deezer. Immerse yourself in this powerful tribute while you're on the go!

Plaques & Memorials

The City of Oxford and Miami University are continuing to put up important plaques and memorial spaces to make it easier than ever for all of us to find the specific spots where Black history in our town has taken place.

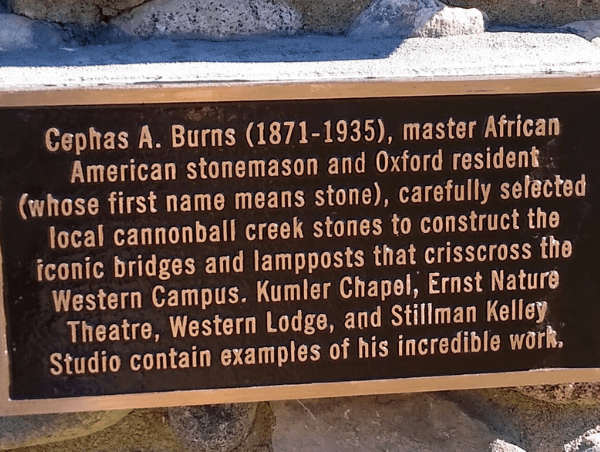

Cephas Burns Plaque

Cephas Burns was a master stonemason in Oxford and was responsible for many of the gorgeous stone footbridges, lamp posts, and buildings that make Miami University's Western Campus so unique.

In March of 2021, the Western College Alumnae Association dedicated a plaque in honor of Cephas Burns which can now be found on the Western Campus footbridge running south of the Western Dining Commons.

For more photos of the plaque, including a close-up photo so you can read the inscription, click here.

Freedom Summer Memorial

Located across from Peabody Hall on Miami University's Western Campus is the Freedom Summer Memorial, built in 2000 to honor the lives and bravery of the 1964 Freedom Summer volunteers.

This stunning memorial features stone benches with engravings that chronicle the events of the entire summer. There are also three trees fitted with steel sculptures to honor James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, the three volunteers who were murdered after leaving Oxford to do work in Mississippi.

Freedom Summer Digital Map

Nellie Craig Walker

Nellie Craig Walker was an Oxford native and the first Black graduate from Miami University. In 1905, she earned her two-year teaching certificate and was the first Black educator to student-teach in the community's public schools to a mixed-race class.

On February 24, 2021, Miami University officials dedicated the former Campus Avenue Building as Nellie Craig Walker Hall located at 301 S. Campus Avenue.

For more information about Walker and her impact, please click here.

Truth & Reconciliation Marker Source Information Overview

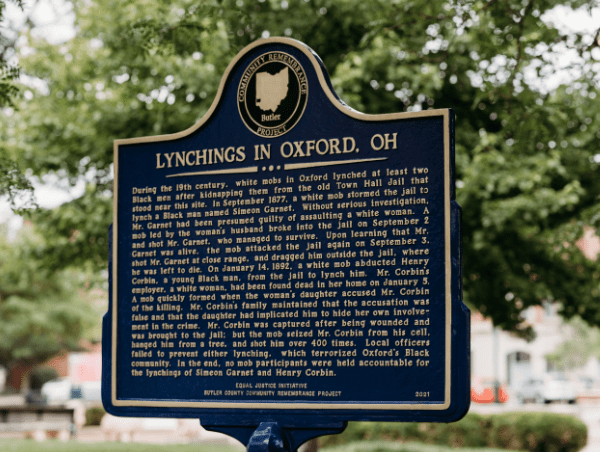

On June 21, 2021 during the 10th Annual National Civil Rights Conference at Miami University, this new plaque was erected in the uptown Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Park to honor two lynching victims from Oxford's past: Simeon Garnett + Henry Corbin.

Extrajudicial lynchings occurred in Oxford in 1877 and 1892, resulting in the deaths of Simeon Garnett and Henry Corbin. Surviving sources of information on both lynchings primarily consist of local and regional newspaper coverage. Despite the fact that these newspapers offer openly prejudiced, graphic, and sensationalized accounts of the events which took place, they also provide the greatest amount of information available for historical analysis. Besides the newspapers, other primary and secondary information sources have also survived, including official death records, books and articles on the lynchings, oral histories, and other vital and genealogical records. Please contact the Smith Library of Regional History to obtain this information.

Additional Black Historical Figures

Considered the best documented Underground Railroad site in the Oxford area. Born in Butler County in 1819, John S. Jones is known to have aided his father, Jack Jones, as an Underground Railroad operator. Together they helped enslaved people escape the South through Hamilton and up to the Quaker communities of West Elkton, Ohio, as well as Richmond, Indiana.

According to the family’s oral history, enslaved people would follow the Great Miami River north from the Ohio River all the way to Jack Jones’ home in Hamilton. From there, he would direct them to follow the railroad tracks that had been laid between Hamilton and Oxford. They would eventually find themselves at the farm residence of John S. Jones on Booth Road where they’d be given refuge before the next part of their journey.

In 1852 Jones also became the first Black American to testify in a Butler County Court. He continued to live in his farm residence on Booth Road until his death in 1898.

The Miller Family has long had an important and influential history in Oxford. Simon Miller, born in 1900 in Alabama, came to Cincinnati in 1905 and moved to Oxford with wife Lazelle Jones Miller (granddaughter of John S. Jones) in 1918. He worked on the construction of Ogden Hall at Miami University and remained at Miami University as a custodian in the Physical Education Department for forty-five years. He was an active member of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church, a 32nd Degree Mason, and a charter member of the Oxford branch of the NAACP. He also served as president of the branch, leading the legal challenge to compel the village of Oxford to admit African Americans to the Oxford Municipal Pool in 1950. Miami University’s Department of Health and Physical Education for Women gave him an honorary graduate degree because of his dedication to influencing prospective drop-outs to stay in school. He died at the age of 87 in 1988.

Simon’s son, Arthur Miller, was born in 1921. He was an activist from a young age, refusing to use the “colored” bathroom in elementary school. A World War II veteran, Arthur achieved the rank of Sergeant during his four years in the U.S. Army. Upon returning home, he enrolled at Miami University and received a bachelor's degree in 1949. He was the first Black American allowed to practice-teach at Miami’s McGuffey Laboratory School, and later became the first Black American to manage the university’s central food store. Arthur followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming active in the local NAACP branch and leading it as president for more than 20 years. Arthur’s many accomplishments include supporting civil rights workers during the Mississippi Summer Project, later known as Freedom Summer 1964. Additionally, he served on the Oxford Village Council for six years and was Vice Mayor for two. He died at the age of 85 in 2007.

Anna Estella Hasty

Anna Estella Hasty, born in 1876, was the daughter of Peter and Fannie Proctor Bruner. A resident of Oxford her entire life, Hasty was an early graduate of the Oxford Public School. She was an active member of the Bethel A.M.E Church and its missionary society (which, after Hasty’s death, was renamed the Estella Hasty Women’s Missionary Society). She was, additionally, a member of the Ladies’ Improvement Club and the Oxford Senior Citizens.

Shortly after 1935, Hasty became a writer for the Oxford Press, a job she continued for over 25 years. She was commended for faithfully reporting the news, often walking her reports uptown herself. Even after her retirement, she would continue to phone news to the press.

Hasty passed away at the age of 90 in 1966. She is buried in Woodside Cemetery.

LYNCHING

Simeon Garnett + Henry Corbin

We remember and honor the lives of two Black Oxford citizens, Simeon Garnett and Henry Corbin, lynched in 1877 and 1892 respectively. In each instance, after being accused of a crime, each man was arrested by law enforcement. Despite the best efforts of village officials to prevent mob violence, the men were publicly lynched. In 2019, a memorial ceremony was held in Oxford’s uptown parks, close to where each man was murdered. In 2021, a commemorative marker was installed at the same site.

Acknowledgements

Information gathered and summarized by Taylor Meredith at Enjoy Oxford with special thanks to Valerie Elliott for contributing her knowledge of Oxford history.

First Printing: May 2020

Second Printing: September 2022 with funding by W. E. Smith Family Charitable Trust

Photographs by Miami University Communications and Marketing, Miami University Recensio, Paul Schult, Gilson P. Wright, Frank R. Snyder, and others whose names are not known.

For more information on Oxford history, visit:

The Smith Library of Regional History

441 S. Locust St.

(513) 523-3035